Neo-Realism to Socialist Realism

back to Constructivism (21 - 28)

Although the Futurists and, later, the Constructivists claimed to have produced a revolution

in art comparable to the political revolution of the Bolsheviks, neither the masses nor the

Bolshevik leaders found their abstract art much to their tastes. Throughout the 1920s,

various groups of artists inclined to figurative painting opposed the avant-garde groups,

both in the realms of art and artistic politics. At first, the political authorities stayed out of

such debates, but, by the 1930s, they openly began supporting neo-realist trends. After the

famous Writers' Congress of 1934 (which was followed by analogous Congresses for

other branches of art), Socialist Realism was proclaimed to be the only acceptable method

for Soviet art. Although the term was in practice loosely defined, it was claimed that

Socialist realist works were to "display a historically concrete representation of reality in its

revolutionary development." The first part of this definition pointed to the need for a realist

aesthetic, while the latter asked for a certain optimistic idealism. Avant-garde artists found

exhibition and publication outlets increasingly hostile to their work, until by the mid-1930s,

the avant-garde effectively disappeared from sight.

#31

#31

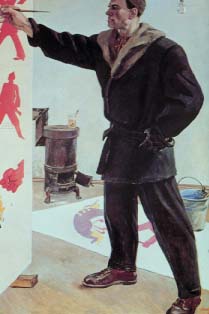

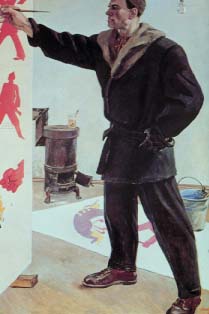

Alexander Deineka (1899-1969) stood somewhere in the middle of

these debates, sometimes associating with the Constructivists and at others aligning

himself with various neo-realist groups. This heroic, monumental portrait of

"Mayakovsky at the ROSTA Agency" (1941), shows Deineka in a socialist realism mode.

Mayakovsky towers over all, a symbol of socialist purposefulness. He is engaged in

painting Bolshevik propaganda posters, an activity in which he was sometimes engaged in

the years immediately after the Revolution.

#32

#32

Isaak Brodsky (1884-1939) was one of the young artists attracted to

the neo-realist group that called itself the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia.

The primary goal of the group was to depict revolutionary Russia by painting realistic

canvases devoted to such topics as Russian workers, soldiers, and political figures. In their

return to tendentiousness, they consciously attempted to revive the traditions of the

Wanderers. Brodsky made something of a specialty for himself in paintings of the greatest

revolutionary leader of them all, Vladimir Ilich Lenin. Brodsky clearly strove to humanize

rather than monumentalize the leader, as this "homey" picture of Lenin at work illustrates.

#33

#33

Alexander Gerasimov's painting "Black Earth" (1930) is an excellent

example of neo-realist style. The tractor was, of course, one of central Soviet symbols, an

illustration of the technological progress that had, supposedly, been introduced in the

countryside by the Bolshevik regime.

#34

#34

Sergei Gerasimov's "Collective Farm Harvest Festival" of 1937 is a

perfect example of high socialist realism. The happy collective is presented with great

realistic detail (not that any collective farm actually looked like this). Bodies are muscular,

abundant food is on the tables. The whole is bathed in a warm glow of light, symbolizing

the bright socialist future which appears to have more or less been achieved. The final

scene of Kirshon's play "Bread" should have looked something like this.

#35

#35

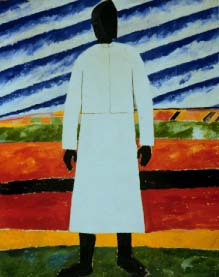

In 1928 Malevich embarked on a cycle of paintings that differed

radically from the work he had produced in his previous period. Turning away from the

abstract, geometric shapes of his suprematist paintings, Malevich returned to figurative art,

in a series of canvases which, for the most part, depict volumetrically-shaped peasant

figures "en face" against spartan backgrounds. The figures themselves are distinguished by

the bright colors of their clothing as well as by a complete (or, in some cases, almost

complete) lack of facial features. As regards their theme, their concern with figuration, and

their monumentality, Malevich's second series of peasants can be read as an attempt by the

artist to find a compromise with the leading trends of Soviet art. This painting, "Girls in a

Field" (1928-32) disturbs the viewer not just because of the absence of facial features, but

also because of the lack of interaction between them. Compare this painting and the one

that follows with Malevich's earlier peasant paintings (#s 38, 39).

#36

#36

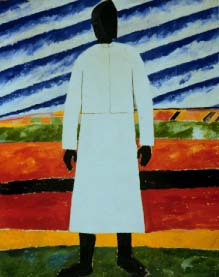

Perhaps equally disturbing is Malevich's "Complex Presentiment"

(1928-32). The beard and the distant silo allow us to recognize a peasant scene, but it is

impossible to provide a psychological reading of the scene.

#37

#37

This is another example of Malevich's peasant series of 1928-32.

#38

#38

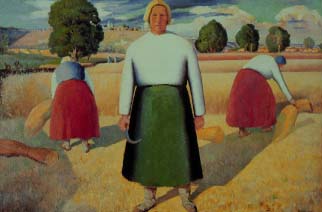

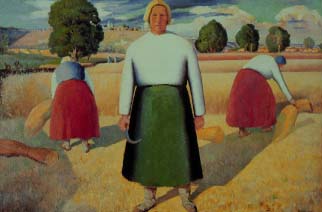

The bodies of the women in "Reapers" (1909-10) are rendered

volumetrically ( a technique borrowed, perhaps, from the French artist Fernand Léger).

The vibrant colors of their clothing are typical of Russian avant-garde painting, while the

massive shapes would later be repeated in a more disturbing series of canvases painted at

the end of the 1920s.

#39

#39

This painting of a Dacha resident by Malevich was probably executed

in around 1910.

#31

#31

#32

#32

#33

#33

#34

#34

#35

#35

#36

#36

#37

#37

#38

#38

#39

#39