Constructivism

back to The Russian Avant Garde (12 - 20)

In the late teens and early twenties, Soviet artists and designers attempted to put their talents

to use for the new communist state. Most abandoned easel painting, even in its most

radical forms, as overly bourgeois, and turned instead to design. The general slogan of

these "constructivists" was "Art into Life" and their goal was, as Tatlin put it, "to unite

purely artistic forms with utilitarian intentions." In their most extreme formulations, the

constructivists announced "Art is finished! It has no place in the human labor apparatus.

Labor, technology, organization...that is the ideology of our time." (For full texts of

constructivist manifestoes, see Bowlt, pp. 205-261) Despite the ostensibly utilitarian

nature of the Constructivists' concerns, the vast majority of their projects were utopian in

nature and never reached a mass audience.

#21

#21

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) was a student of both Malevich

and Tatlin in the period just before the Revolution. This "Collage" of 1919 combines the

dynamic vertiginous axis and strict geometrical shapes typical of Malevich's later

suprematist works with the use of different materials pioneered in Russia by Tatlin.

During the 1920s, Rodchenko became one of the leading constructivists, and turned away

from painting to photography, furniture and poster design. In 1929, he designed costumes

and sets for Meyerhold's production of the second half of Mayakovsky's play "The

Bedbug".

#22

#22

Another major artist influenced heavily by Malevich and, to a lesser

extent, Tatlin was El Lissitsky (1890-1941). Lissitsky was originally trained as an

engineer and architect. His series of "prouns" (this one is labeled #30), experiment with

Malevich-like forms which are drawn with all the precision an architect could muster.

They hold a delicate and tense balance between seeming suspended in mid-air and about to

collapse.

#23

#23

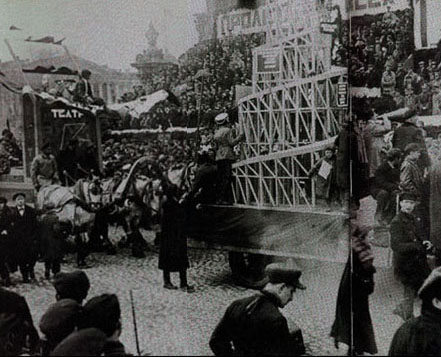

Like many other artists who supported the Bolshevik coup of October

1917, Lissitsky actively attempted to advance the ideas of the state by bringing his art to the

masses. This propaganda, or agitational (agit-prop) panel was photographed on a street in

Vitebsk in 1920. The inscription on the panel reads "The Machine tool depots of the

factories and plants await you. Let's get industry moving."

#24

#24

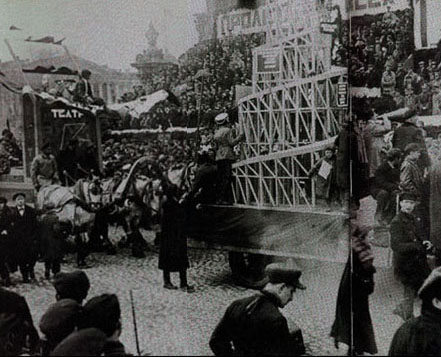

In 1919 and 1920, Vladimir Tatlin produced sketches and a model for

what was projected to be a Monument to the Third International. This utopian design, so

typical for the frenzied mood of Russians in the years immediately following the Bolshevik

revolution was, in theory, to have been taller than that great symbol of modernity, the Eiffel

Tower. Its spiraling structure, however, was to lend the Monument a structural dynamism

lacking in Eiffel's more symmetrical (and more stable) design. In theory, the Monument

was to house a telegraph office, and other office space, but Tatlin, who was no architect,

did not even attempt to work out the engineering problems that would have had to be

overcome. Instead, like so many other early Soviet projects of utopian intent, Tatlin's

tower (as it came to be called) never went past the planning stages. The model was

exhibited--and photographed--in Petrograd in November 1920, at the same time as the

mass theatrical action, "The Staging of the Winter Palace", was performed.

#25

#25

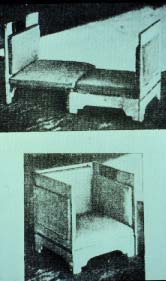

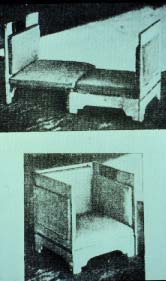

The designer Sobolev contributed this early "sofabed" meant for use in

the relatively cramped apartments of the new Soviet state. Sleek, multi-use designs of this

sort played a central role in the constructivist sets that Meyerhold and Tairov would use so

successfully in the early 1920s.

#26

#26

Varvara Stepanova (1894-1954) was the wife of Alexander

Rodchenko, and a major constructivist artist and designer in her own right. In this 1923

photograph she poses in sports clothes of her own design. Such clothes were meant to fit

in with the general ethos to create simple and functional, yet aesthetically pleasing quotidian

objects for the general public. Unfortunately, most of these projects never made it off the

drawing board into mass production, either for technical, economic, or political reasons.

#27

#27

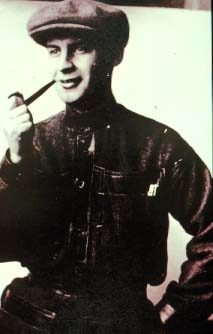

In this 1925 photograph, Alexander Rodchenko poses in a suit of

worker's clothes of his own design.

#28

#28

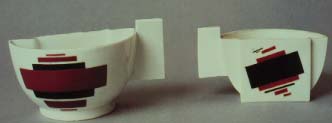

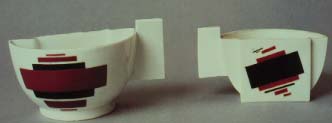

Even Malevich got into the design act. This photograph depicts two

teacups painted with suprematist designs. The actual execution of the painting was by two

of Malevich's students Ilia Chashnik and Nikolai Suetin. Although the cups are definitely

striking, their utility is somewhat questionable, and it is unlikely that the designs would

have been to the liking of the average Soviet coal-miner. Perhaps not surprisingly, such

china was never mass produced.

#29

#29

This photograph shows Malevich at the "Experimental laboratory" at

the State Russian Museum in Leningrad sometime in the 1930s. He is working on one of

his "architectons" -- three-dimensional spatial models vaguely reminiscent of architectural

projects, although none was ever built.

#30

#30

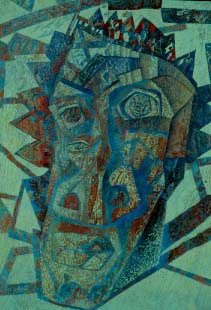

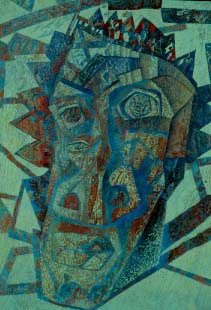

While the best-known lines of Russian avant-garde artistic

development passed through Malevich and Tatlin, Pavel Filonov (1883-1941) worked

slowly and painstakingly to develop a highly personal style. Although he started his career

in the Futurist camp (and contributed to the design of Mayakovsky's "Vladimir

Mayakovsky. A Tragedy" in 1913. Like most of the Futurists, Filonov welcomed the

Bolshevik coup. Throughout the 1920s, Filonov developed a school of what he called

"analytical art" which he practiced and taught to a devoted band of followers. His

paintings, like this "Head" (1925) are distinguished by great delicacy and minute

brushwork. Every inch of the painted surface is filled with an abundance of detail which

flows together to create the whole. Filonov was fascinated by the grotesque, by the art of

children and the insane.

#21

#21

#22

#22

#23

#23

#24

#24

#25

#25

#26

#26

#27

#27

#28

#28

#29

#29

#30

#30