Symbolism

back to Russian Realism (1 - 6)

By the mid 1880s, the Russian realist movement reached something of a watershed. Of

the great writers, Dostoevsky and Turgenev were dead, and Tolstoy had renounced art in

favor of religion. By the early 1890s, a series of new artistic trends began to appear.

Influenced initially by French literature and art as well as by the art of Romanticism

(Russian and European), the Russian decadents and symbolists turned from novelistic

prose to lyric poetry and, eventually, to drama. They also rejected the commonly-held

belief that art should serve social progress. Rather, they posited the artist as a free godlike

figure whose life and work could point the way to the ideal future. In the visual arts, we

can see how abrupt the turn away from realism was if we look at the painting of Mikhail

Aleksandrovich Vrubel (1856-1910).

#7

#7

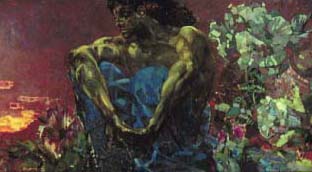

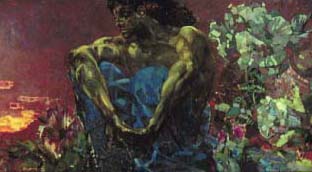

Mikhail Vrubel "The Demon Seated" (1890). The subject of this painting

is the hero of Mikhail Lermontov's Romantic narrative poem of the same name. This

work, written in the late 1830s tells the story of a byronic demon fated to love a Georgian

princess, who dies as a result of his kiss. She is saved by angels, while he is doomed to

spend eternity alone. This over-heated story fit perfectly with the Romantic temperament,

but would have been anathema to realist writers and painters. Vrubel described the Demon

as "A spirit which unites in itself the male and female appearances, a spirit which is not so

much evil as suffering and wounded, but withal a powerful and noble being." Note the

otherworldly expression in the Demon's eyes (as opposed to the expression on Turgenev's

face #1, for example), symbolic of the existence of a world beyond that of the everyday.

Note also the background, which is filled with such symbolically-laden images as sunset,

fire (which stands for the end of the world), as well as aggressively non-realistic flowers.

#8

#8

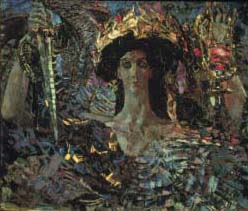

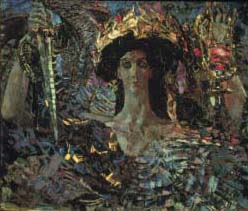

Mikhail Vrubel "The Six-Winged Seraph" (1904). In this painting,

Vrubel uses an image derived from Alexander Pushkin's poem "The Prophet" (1826). In

Pushkin's poem, the figure of the poet is described as dragging himself through a spiritual

desert. He is met by a six-winged seraph who touches the poet's eyes, ears and lips,

opening to him the mysteries of the world, normally hidden from human eyes. Finally, he

rips out the poet's heart and replaces it with a burning coal. After this operation, the poet

hears the voice of god who tells him: "Arise, poet, and see, hear/Fulfill my will/And

passing through the land and seas/Ignite the souls of man with words." The notion of the

artist as the mediating force between the phenomenal and noumenal worlds was

immensely popular among the symbolists.

#9

#9

Viktor Borissov-Mussatov (1870-1905) spent his formative years in

Paris working in the studio of the French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. He was

influenced not by Moreau's grotesques, however, but by the more lyrical and nostalgic

paintings of Puvis de Chavannes. In all of Borissov-Mussatov's mature work we feel a

kind of elegiac melancholy that harmonized perfectly with a certain strain of provincial

symbolist thought. Borissov-Mussatov favored mysterious feminine figures whose poses

suggested some kind of otherworldly concerns, as in this painting, entitled "Spring"

(1901). His palate, filled with greens and blues is typically symbolist as well.

#10

#10

L�on Bakst (1866-1924) began his career as a kind of junior associate of

the Wanderers. By the 1890s, however, under the influence of modern French painting, he

abandoned that aesthetic. A trip to North Africa in 1897 opened the exotic world of the

Mideast to him, and he scored his greatest success as a designer of opulent orientalist

costumes and sets for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, most famously "Sch�h�razade" (1910).

He was also the designer for many of the Ballets Russes most famous ballets on classical

themes, including "Daphnis and Chlo�", and Nijinsky's notorious "Afternoon of a Fawn".

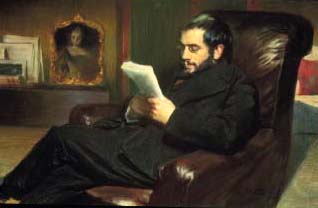

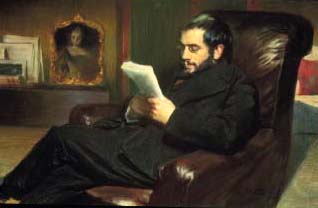

After the Revolution, Bakst remained in Europe. In the late 1890s, he was one of the

leading members of the so-called World of Art group, that formed around the artist

Alexandre Benois (1870-1960), depicted in this 1898 portrait. The painting itself, by the

way, shows Bakst's connection with the wanderer aesthetic (compare to the portrait of

Turgenev by Perov, #1 ).

#11

#11

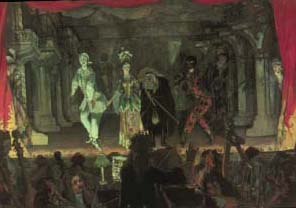

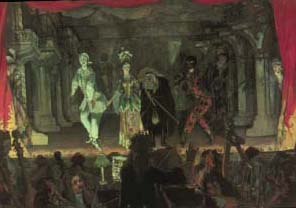

Alexandre Benois (1870-1960) was the artistic moving force behind the

World of Art movement. It originated in a circle of like-minded friends who dubbed

themselves the "Nevsky Pickwickians", and they devoted themselves to rescuing those

artistic traditions that had been neglected or denigrated by the Wanderers. Rather than

trying to create a purely Russian art, they opened themselves to the best of contemporary

European painting, and they promoted the pictorial heritage of the Russian middle ages and

18th century. The culmination of the World of Art group's activities, was the publication

of the luxurious journal of the same name which was published between 1898-1904. This

journal was the leading organ for the communication of modern ideas on art as a form of

mystical experience. Its pages were open to the leading symbolist writers, and its splendid

color illustrations reproduced the work of contemporary Russian painters as well as leading

practitioners of Art Nouveau from Western Europe. Benois was one of the journal's

leading critics (for a sample of his critical writing, see John Bowlt, "Russian Art of the

Avant Garde" pp. 3-6), and one of his particular interests was the tradition of the Italian

A

commedia dell'arte, which he promoted both in his artistic work--as in this gouache of

1905--and in his criticism. This interest would culminate in his designs for the Ballets

Russes production of "Petrushka" in 1911 (see illustrations # 42-44, 46-47, 49-50 ).

#7

#7

#8

#8

#9

#9

#10

#10

#11

#11